Selection of the Burial Site

The issue of Ulysses S. Grant’s burial site immediately arose upon his death. A figure of worldwide renown, Grant was recognized as one of history’s great captains and the pre-eminent American of his time. It was widely understood that his final resting place should reflect his stature.

Although inclined to choose West Point as a burial site, Grant ruled out this option out of concern that his wife Julia could not be buried beside him when her time came. While dying of throat cancer, Grant indicated to his oldest son, Fred, several possibilities for a burial site: The one essential condition Grant established was that a place be reserved for his wife at his side.

St. Louis

Grant had lived here for several years before the Civil War.

Galena, Illinois

This was Grant's hometown from before the Civil War until after his presidency.

New York City

Grant lived here the bulk of his last four years. He was grateful to the people of New York for their kindness and generosity after a financial disaster hit him and his family.

Burial

After struggling with throat cancer for months, Grant died on July 23, 1885, in a cottage on Mount McGregor, New York, near Saratoga. Mayor William R. Grace (who would later serve as president of the Grant Monument Association) offered to set aside land in one of New York City’s parks for burial, and the Grant family chose Riverside Park after declining the possibility of Central Park.

Riverside Park included one of the highest points of elevation in Manhattan overlooking the Hudson River. The park was in its formative years at the time, and it was believed that the tomb would stand as a central theme for future park development.

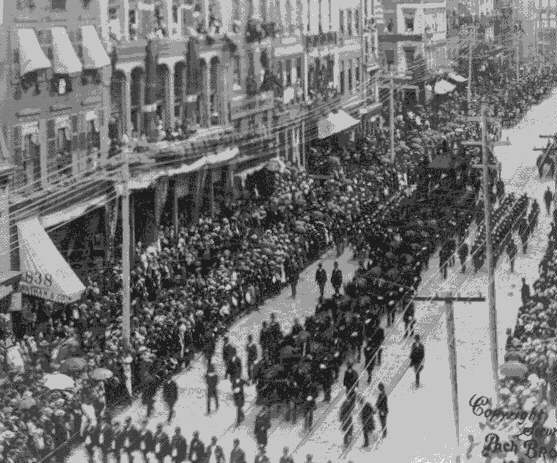

Grant’s funeral was one of the greatest outpourings of public grief in history. A large funeral parade marched through New York City from City Hall to Riverside Park. It had 60,000 marchers, stretched seven miles, and took up to five hours to pass. Realistic estimates of the spectators who witnessed the parade reached 1.5 million, making this the largest assembly of people at one time and location in the history of the North American continent up to that time.

The funeral was attended by numerous dignitaries, including President Grover Cleveland, his cabinet, the justices of the Supreme Court, the two living ex-presidents (Hayes and Arthur), virtually the entire Congress, and almost every living figure who had played a prominent role during the Civil War.

Civil War veterans from both North and South took part, reflecting the high esteem in which he was held throughout a reunified country. General Winfield S. Hancock led the procession, and Grant’s pallbearers included former comrades—General William T. Sherman, General Philip H. Sheridan, and Admiral David D. Porter—as well as former Confederates—Generals Joseph E. Johnston and Simon B. Buckner.

The funeral procession made its way from City Hall up Broadway, then west on 14th Street past Union Square, then north on Fifth Avenue, then west at 57th Street, then back up Broadway, then west on 72nd Street to Riverside Drive (where Riverside Park begins), then up Riverside Drive to the temporary tomb in Riverside Park near the intersections of 122 and 123 street. The makeshift structure was designed by Jacob Wrey Mould, chief architect of New York City’s Department of Public Works, and essentially copied the design of the first tomb of railroad builder Henry Meiggs near Callao, Peru. With outside dimensions of 17’ x 24’, it consisted primarily of red bricks with black brick trim and a semi-cylindrical asphalt-coated brick roof. Grant’s remains would rest in that temporary vault until the construction of a permanent tomb.

The Grant Monument Association

The Grant Monument Association (GMA) was formed within days of Grant’s death to secure a fitting tomb.

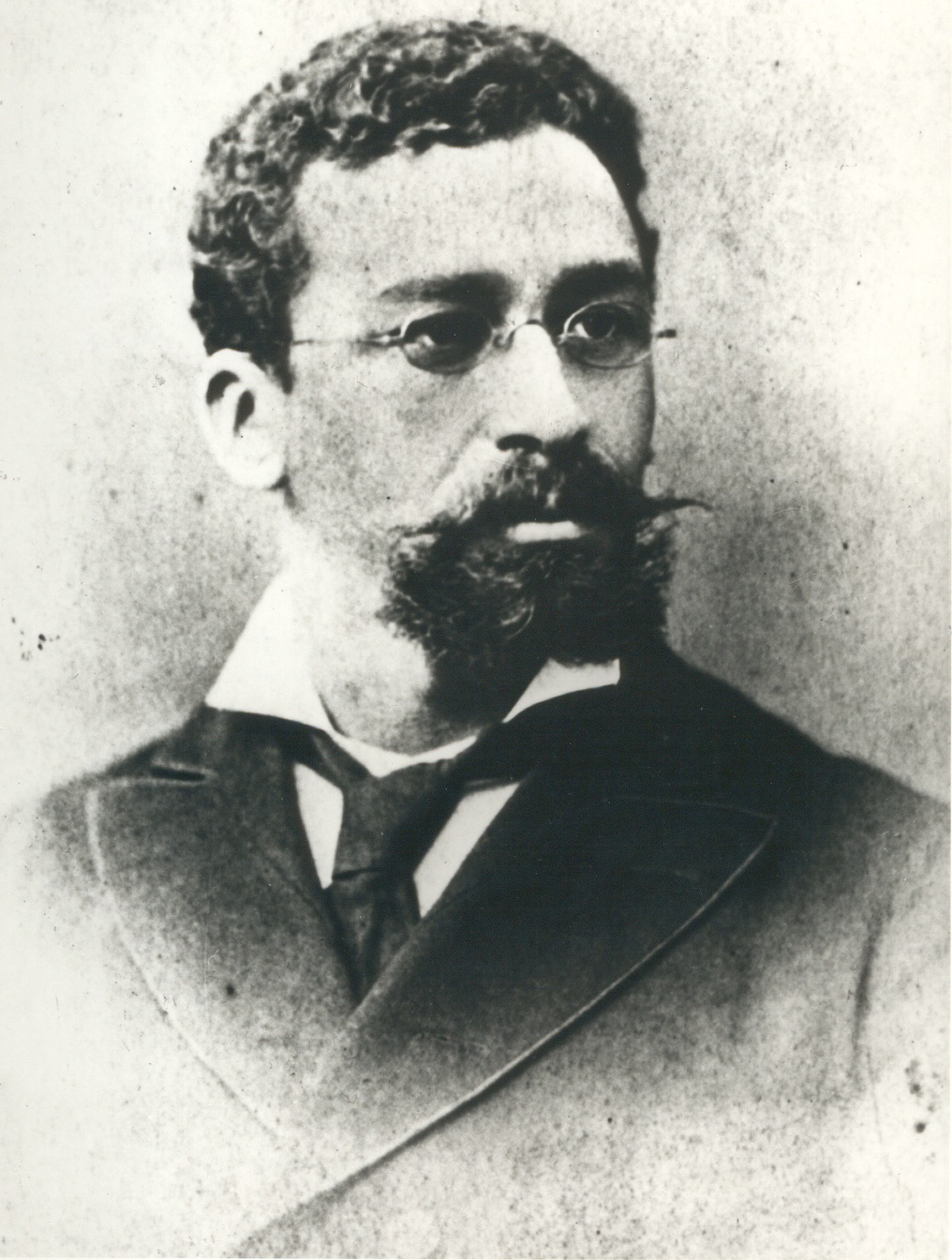

Former President Chester A. Arthur was its president. Richard T. Greener, first black graduate of Harvard and political supporter of Grant, served as the GMA’s first secretary (1885-1892).

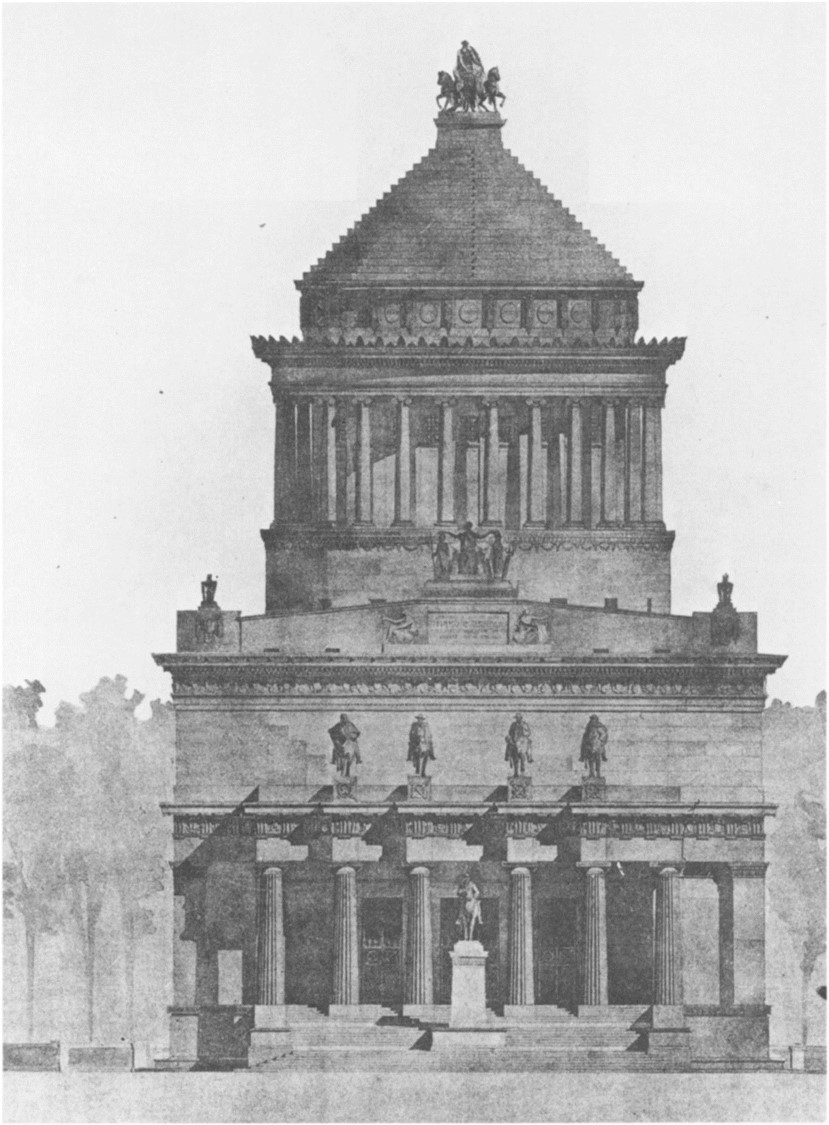

The GMA held two competitions, in 1888 and 1890, in search of a suitable architectural design for Grant’s Tomb. It ultimately selected a design submitted by architect John H. Duncan.

Over $600,000 would be raised by 90,000 people to construct the Tomb.

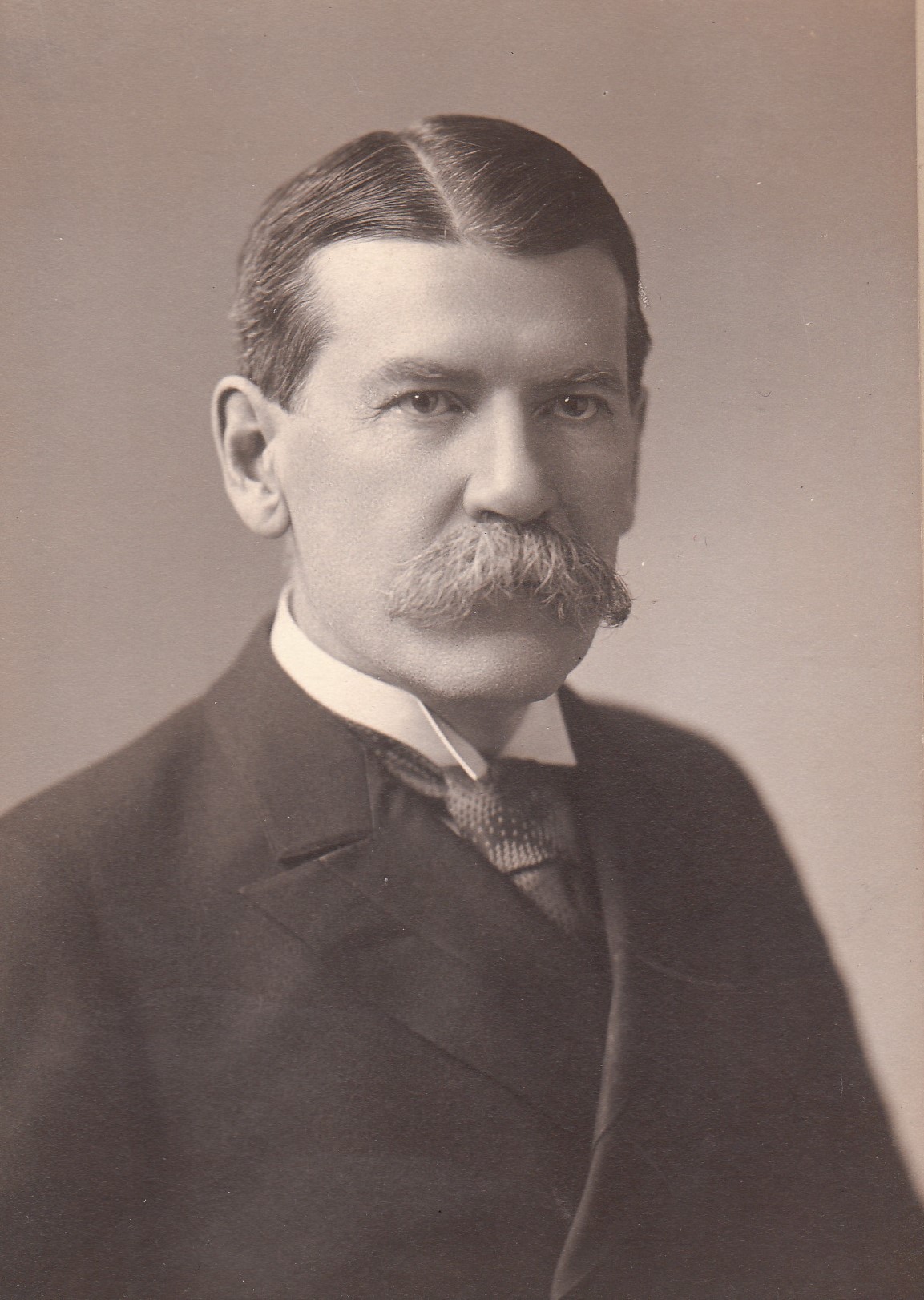

In 1892, General Horace Porter became the fifth president of the Grant Monument Association in 1892. Porter had served as an aide de camp to Grant during the last year of the war and briefly as his presidential secretary. He played an instrumental role in the most critical stages of funding and constructing the monument. Porter later served as ambassador to France under Presidents William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt (1897-1905). He served as president of the GMA until shortly before his death in 1921.

Construction & Dedication

Ground was broken for the Tomb on April 27, 1891. On April 27, 1892, the 70th Anniversary of Grant’s birth, President Benjamin Harrison laid the cornerstone of Grant’s Tomb. Over 8,000 tons of granite would be used for construction.

On April 27, 1897, the 75th Anniversary of Grant’s birth, Grant’s Tomb was dedicated. The occasion was a full public holiday, Grant Day, and attracted a throng of spectators to rival Grant’s funeral nearly twelve years earlier.

The dedication day parade featured 55,000 marchers, led by the West Point corps of cadets, and was observed by about one million onlookers. President William McKinley and Horace Porter addressed an enormous crowd as Mrs. Grant and her family observed the ceremony.

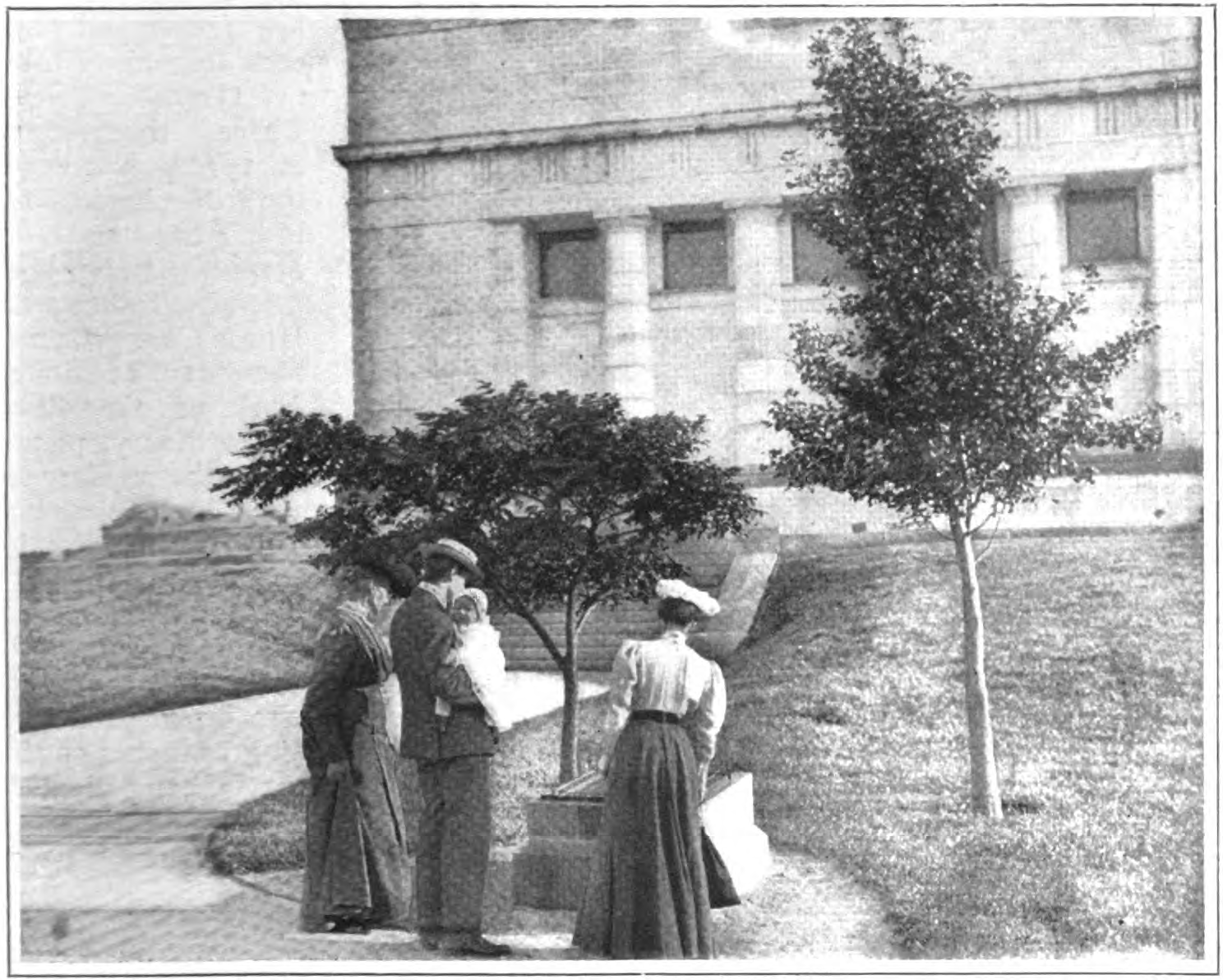

In May 7, 1897, former Chinese Minister Yang Yu, representing Li Hung Chang, the Chinese viceroy who had become acquainted with Grant during the latter’s world tour, planted a ginkgo tree on the site of Grant’s temporary tomb. That tree would soon be followed by a witness tree, a Chinese cork, and a plaque with inscriptions in Chinese and English.

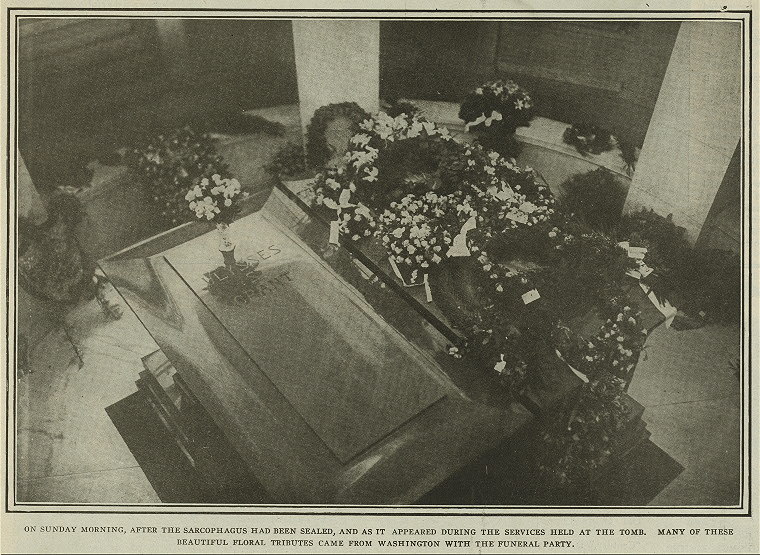

Julia Grant died on December 14, 1902, in Washington, D.C., and her remains were interred beside her husband’s in a twin sarcophagus.

Early History

Besides being recognized as one of the nation’s greatest monuments, Grant’s Tomb was one of the most popular buildings in the country. In its early days, the Tomb’s annual visitation often exceeded 500,000 (peaking in 1906 at 607,484). Its visitation exceeded that of the Statue of Liberty through World War I.

In 1928, architect John Russell Pope proposed a number of developments at Grant’s Tomb, including the addition of an equestrian statue in the plaza and a pediment above the portico as illustrated here:

However, the Great Depression would hinder efforts to raise necessary funds for the most ambitious projects. Nonetheless, in 1938-1939, a number of developments were pursued with support of the Works Progress Administration (WPA):

- Installation of busts in the crypt depicting Grant’s most esteemed lieutenants during the Civil War.

- Artist Dean Fausett painted murals in both reliquary rooms featuring allegorical figures and the theater of the Civil War, with locations of Grant’s battles highlighted.

- Re-landscaping and modifying of the surrounding plaza.

During the 1950’s, the GMA, suffering from a declining membership and aging leadership, decided to transfer control over Grant’s Tomb to the federal government. The National Park Service took over the site in 1959 and officially named the monument the General Grant National Memorial.

The GMA dissolved in 1965, though not before securing the installation of mosaic murals by Allyn Cox in the three lunettes, which were dedicated in 1966.

This was the last major addition to the monument, but the story of Grant’s Tomb was far from over.